Here is one of my questions:

In the sixteenth-century icons I'm writing about, there are lots of symbols. A ladder in the hands of Mary symbolizes, by synecdoche, Jacob's ladder, and by extension symbolizes a link between heaven and earth (=Mary), and the fact that the Old Testament prefigures the New. Complex geometrical aureoles symbolize a Burning Bush, and also, by means of Pythagorean number theory, eternity, and also the energies of God, and maybe Divine Wisdom.

Lots of theologians and art critics object to these piles of symbols-- they say things like "the realism of the Gospel is replaced by allegorism," and "a tragedy for Russian painting, which lost the true depth of its spiritual image and acquired in exchange an external beauty and a ritual formula," and complain that "revelation in the world [is] a series of events and not only a chain of symbols."

This all seems very true, and I'm all ready to look sternly upon religious allegory and symbolism, demanding portraiture and historical prototypes. But then the symbols are often cool, and I don't really see why prophets and mystics should get to write in symbols but painters shouldn't be allowed to paint in the same way. In answer to a rather puritan Ecumenical Council's edict forbidding depictions of Christ as a lamb, or as anything but the historical Jesus, this 14th-century patriarch writes: "And then in the age of the new covenant when the shadow of the Law has passed and all is fulfilled in grace and truth, then we find that the Lord himself speaks indirectly and through parables and teaches the apostle the divine mysteries through sacred symbols."

The question is: does an increase in symbolism in art signal spiritual and cultural decline, a sort of diffusion of the intensity necessary to represent ultimate truth in simple portraits, with only harmony of line and color? The question seems generalizable: in writing, in other art forms, even in thought itself, is there an intrinsic danger in symbolism? I don't think I can categorically deny the potentially great power of a symbol, whether based on a historical prototype or not, but it certainly seems the case that one can go overboard with symbols, and the results are cluttered and confusing. Look at this icon, and try to figure out what the heck is going on:

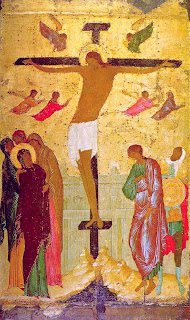

Here is an icon more admired by theologians and art historians, supposedly without allegory:

When do accumulations of metaphors not equal the sums of their subtleties? The question is not rhetorical, I expect everyone who reads this to answer.

10 comments:

I read it. I'm hoping that nights organizing Safeway's supplies of macaroni and cheese and tuna fish cans will illuminate all of life's answers. Namely, "When DO accumulations of metaphors not equal the sums of their subtleties?" Like seriously WHEN...DO THEY...Also, the first icon is truly very alarming. I don't feel calm or close to god/God/G-d/Jesus (pronounced Geezus not Heysus like baseball players). This post has lost any sort of coherence or usefullness.

Here's a semantic distinction: the danger is not symbolism but excessive referentiality, particularly self- or intertwining-referentiality. Everyone is familiar with cultures that develop insularly, whether on online forums, the academy, or geographically isolated religious communities: they accrue their own set of symbolic jargon, short hand, self-congratulatory expertise that poses a barrier to newcomers, ignorant of the native language. I think it's a bit spurious to claim that insular, bewilderingly referential systems are somehow spiritually bankrupt; they are simply less universal, which is only a problem if the religion aspires to universal dispensation. In fact, I think there might be a Western bias at play here - the presupposition that systems that don't aspire to universality are less legitimate. "Symbolism" is far broader, more ambiguous - the symbolic systems your describing all have definite, set references, whereas symbolism can embrace equivocation, ambivalence, subjectivity.

and another thing, comparing those two images: the first is clearly more complicated, but i think the comparison is unfair. the second image seems more straightforward to us because we're all intimately familiar with the symbolism employed: christ on the cross, angels in the background, etc. to an objective outsider, i submit that the array of symbolic meanings in the second image would be just as incomprehensible as those in the first, if perhaps easier to master. also, are the two images the same size and intended for the same general purpose? i wonder, because the first seems to have grander ambitions: it portrays not one scene like the second but four, each admittedly more complex than the single image of christ. here's my extreme analogy: is it fair to compare the sistine chapel to the mona lisa and accuse the former of too elaborate inscrutability?

Both icons are really big and in major cathedrals. They do belong to a church professing universality.

I'm not sure that the symbols I'm describing do have set references: that's pretty much the complaint. I just identified some of the things the symbols could be associated with. You could just as well associate the ladder with spiritual ascent, and maybe you're meant to; the 8-pointed aureole no one has ever figured out, as far as I can tell.

I think the point of the complaint, medieval and modern, about the first icon, is that the medieval Russian audience wasn't much more familiar with the symbols employed than we are. No one knows, exactly, what a seraph nailed to a cross is supposed to refer to, or whether God the Father is portrayed on the icon. Anyway, the whole point of the criticism, which comes from inside the tradition for and in which the icons were painted, is that there is no clear connection between reference and referent, or that the referents are not historically real, so the references are not obviously legitimate. It's a neo-platonic scruple that we are not used to feeling.

I don't think the only issue is confusion, though that is certainly an issue. The main objection is with the very nature of allegory: that discussion of what something is like is a denial of the reality of what it is. Dionysius' icon clearly contains symbols, but (at least according to the painter and his audience) they are symbols rooted in historical reality: an image of the crucified Christ represents the fact that Christ was crucified, and further symbolic meaning (conquering of death, love of God, sacrifice) come afterward.

Oh, and Dionysius is the painter of the second icon.

The idea is that he expressed feelings and ideas just as deep as those of the first icon, but without descending into allegory, just by the lines of his figures and the juxtaposition of his colors.

One cannot truly understand or appreciate the first icon without exploring the central role of Spiderman in it.

Hahaha.

Hey, I read this, I'll write you an email later. I had a response prepared, but your mom's introduction of the spiderman thematic made me rethink some of my conclusions.

Actually, maybe I'll even post the response here when I'm done, as it will be more web-appropriate than the initial.

-Greg

By the way, who is Anonymous? Connect the symbol of your computer-assigned designation to the symbolized of your identity.

Maybe you could get Anonymous to write your paper for you.

Post a Comment